September rolling around again means not only the return of professional football, but also of professional football’s most popular simulacrum, the Madden video game franchise. EA Sports has been releasing a Madden game every year since 1990, though the first game was published in 1988, making this year its 25th; yet, because Madden is typically dated, like one dates cars, the cover of this year’s Madden 25 is labeled “1989-2014.” Close enough, I suppose.

Madden has long been popular because it offers what can be a gratingly realistic, playable version of the U.S.’s favorite professional sport, complete with the option to have one’s coach challenge close referee calls—the player may let the virtual refs deliberate for close to two minutes, or, mercifully, skip to the decision. Successful gameplay depends on the selection of plays from a playbook that varies from team to team; the plays are complex enough that on defense it’s often easier to just choose a play and let the computer control all 11 players rather than risk missing one’s coverage assignment. On offense, big plays are legitimately difficult to pull off. It’s much smarter to call a running play that will get you a solid four yards than to go for a big bomb of a play. It’s all terribly realistic, and not always that much fun.

The obvious point of comparison to this way of approaching sports video games is something like NFL Blitz (1997, N64/Playstation), a game developed by Midway in the era when companies other than EA were able to acquire licensing rights from the NFL and NFLPA (the players’ union). The game pared down each team to seven players (from 11), and disregarded most of the rules that make the NFL what it is. Pass interference, holding, roughing the kicker, excessive celebration, late hits, even out-of-bounds—these penalties as such don’t exist in Blitz. And it is a fantastic game.

My point here isn’t simply to extol the virtues of the far more gleefully violent, cartoonish Blitz over the seriously serious Madden. Instead, I think it’s worth thinking about what it is that so many people like about professional football, and what they like in a video game that recreates it so faithfully. More than any other sport, football is a game of rules: The delineations of what can and cannot be done extend far beyond the usual behavioral prohibitions that form the basis for any sport (e.g., do not use your hands, you must dribble the ball when you move, etc.), into the obsessively contextual (the cornerback may not touch the wide receiver once the receiver has moved five yards beyond the line of scrimmage) and the ambiguously moral (no “excessive” celebrations). Football is a game largely about discipline—not just the mental and physical kind, but the kind that is enforced from above, exacted on individual behavior. It’s a microcosm of power relations.

With the advent of the replay challenge, football extended its rules into the realms of the virtual and phenomenological: The coach’s challenge is to the reality of an event as perceived by another, a reliance on recording technology to reveal the truth of an event misread by faulty human perception. Football rules hold that what matters above all are the rules themselves—the proper regulation of events by an exterior, regularized authority. Every play means little until it’s completed, divided into its component parts, analyzed and reassembled. One may think the game takes place in Soldier Field, but it’s actually happening in a virtual realm only hinted at by the plane of primary colors on which the players intermittently move. The contemporary NFL is not thinkable without the complex recording and broadcasting apparatuses that serve as the foundation of every game played.

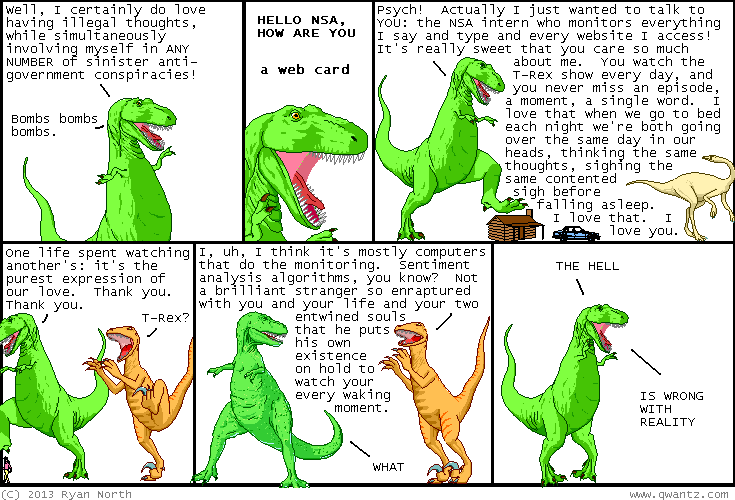

This belief that rules can master reality is, of course, what video games and football have in common. In video games, the rules actually do precede and therefore supercede the (simulated) reality, which is why it’s so funny and odd that football video games have now long included the coach’s replay challenge: Because the same agency (the Central Processing Unit) that has control over the calls the virtual refs make also controls the reality in which they are making calls, errs in judgment about that reality have to be manufactured. The virtual refs actually do, in a sense, make bad calls “on purpose,” as football fans are always wont to believe they do in the real world.

The best and most interesting moments of both football and video games would seem to be those moments that at least seem to defy the constant effort on the part of the “code” and the coders to define experience ahead of time. Long runs by running backs are the best plays in football games because logically the sport is formatted, and its players’ bodies trained, to keep most runs under five yards. Amusing “bugs” are often the most entertaining part of video games—when you call your roommate from the other room to “look at this!”—because they’re the manifestation of a rigorous protocol being violated. Chad “Ochocinco” Johnson is entertaining because he wore a sombrero on the sidelines (and was fined by the league for violating a higher set of extra-gamic rules, or whatever).

If professional football is the most popular sport in the U.S., I think it has a great deal to do with the fantasy of succeeding not just despite the odds—as melodramatic end-of-season recaps would have it—but despite the system, the rules that try to tell you what to expect. If video games are popular, it’s in part because they can indulge such fantasies well. My problem with the Madden franchise is that it sometimes appears as if it believes the appeal of football and video games begins and ends with the playing of informatics, the part of the game where bits clash against bits to produce increasingly esoteric data sets. One ends up with an animated version of what is deceptively called fantasy football, in which there is, of course, little fantasy. “Rational football” would perhaps be a better term, both for the virtual game and increasingly for the “real” one.

Pat Brown is a graduate student in Film Studies at the University of Iowa. No, that doesn’t mean he makes movies; he just likes them a lot.